|

|

ARTS |

CULTURE |

|

Mission Newsletter |

|

Musée Maillol

(61, Rue Grenelle, Paris)

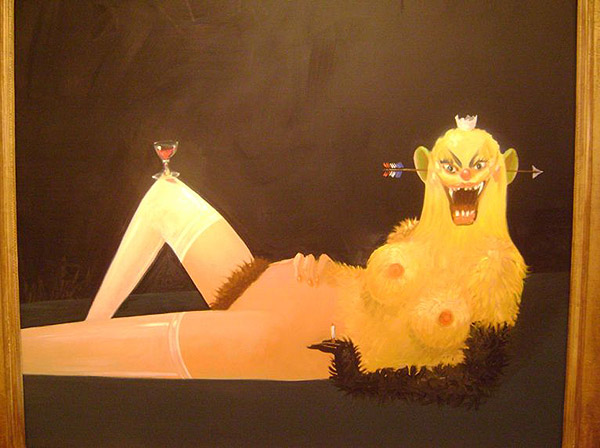

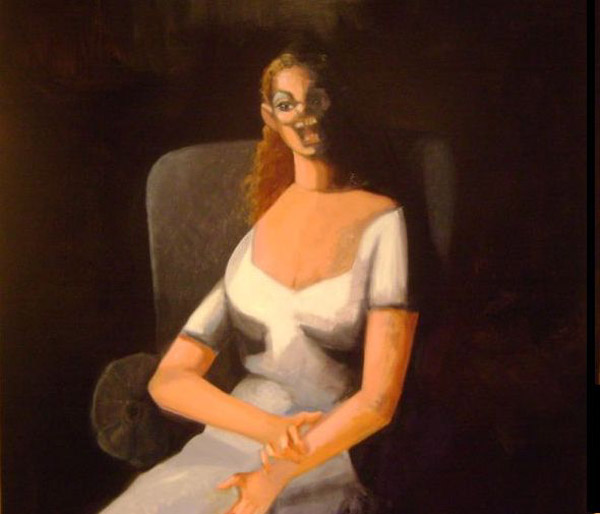

There is more to love about George Condo's art other than his contempt for convention and unabashed repetitiveness -- which reminds us of the one we are most oblivious to, the repetitiveness of the norm. Condo's exhibit at the Musée Maillol in Paris, La Civilisation Perdu, creates an unexpected anthropomorphic link between 1980s New York art (Basquiat, Haring) and ancient philosophy (Epicurus, Diogenes). If Condo's humans are always already not-quite human, they also recall the Greeks' animal metaphors of unapologetic pleasure and libertinage. If the libertine hates the bee for its blind pragmatism ("organicism" as Michel Onfray calls it) and the elephant for its pathological faithfulness, those with a penchant for hedonism find in the hyena and the pig their most appropriate metaphor. Condo's bestial creatures function as cover-ups for the "depravity" of the pig and the hyena, whose unleashed sexuality, like the repressed, always returns. In a kind of purposeful pentimento, Condo allows for the picture beneath the picture (its unconscious?) to rebound on the body of the being depicted. He achieves this often in the shape of an overgrown Adam's apple, or a phallic something protruding from the throat.

It's true that the concept of the pentimento normally involves the reappearance of the painter's initial sketches that were ultimately covered by her final strokes. But Condo makes use of a similar process, rendering the pentimento's "image that returns" the pivotal element of his paintings, calculating the hidden image and, therefore, deforming it. Alberto Giacometti committed similar mindful intrusion by making the sculpture's support a central part of the sculpture itself, confounding diagesis with non-diagesis. In Condo's appropriation of the "what is not supposed to be seen" (the pentimento) as precisely that which is to be seen, his innovation doesn't just inhabit the domain of painting tout court. It echoes the unwelcome, symbiotic and almost causal rapport between beast and human. For Condo's beasts are always engaged in some sort of sexual activity, often an orgiastic one, and completely devoid of conventional beauty. They are hairy, they bear ghastly features, their jaws are lopsided and their gaze is soulless. But mostly, they are alone. Despite their state of perpetual intercourse, theirs is a masturbatory existence.

In The Orgy (2004), one isn't quite sure what limbs are whose. But one is also not sure who is who, for all the depicted creatures look the same. Borrowing from Luce Irigaray's playbook, Condo's beasts hint at a sexual drive that ignores the need for authenticity in the consumed object, i.e. women. Little does it matter who they are -- if it's Jane or Mary or Susan -- or what particularities their limbs hold if from up close they are all inconveniently hairy and excessively porous. Beasts, really. Always already aggressive but always already caged.

|

(c)2008 - 2016 All contents copyrighted by AcousticLevitation.org. All contributors maintain individual copyrights for their works.